Albuquerque, New Mexico

2021

The City of Albuquerque Public Art Program commissioned local artists to create maps of the region. Maps will be part of the City's permanent public art collection.

We invite you to read the Compass Roses Albuquerque Land Acknowledgement.

Events

Compass Roses Exhibition

April 22 – May 22, 2021

South Broadway Cultural Center

1025 Broadway Blvd SE, Albuquerque, NM 87102

Digital Artist Talk

April 24, 2021

Watch the Recording

-

The Red Halo

by Julianne Aguilar

The Red Halo is an immersive audio experience website that explores the fragility of existence on Earth. Two audio pieces guide participants through a park and a mall.

-

Lagrimas del Pueblo

by Lauren V. Coons

Albuquerque has a complex relationship with water. Since the first people settled in the Rio Grande River valley, they have survived on the resources provided by the river while simultaneously enduring the challenges of drought and often devastating floods. As the city of Albuquerque grew, the potential for devastation posed by flooding grew with it, including the risk of pollutants being picked up by flood water and making their way into the Rio Grande. The Albuquerque Metropolitan Arroyo Flood Control Authority (AMAFCA), responsible for the development and maintenance of Albuquerque’s flood control system, has developed a unique and fascinating system for preventing risks to life and infrastructure caused by flooding while working to mitigate the risks of pollution from storm water to the Rio Grande. The relationship between people and water in Albuquerque in many ways reflects the stories of settlement in the Rio Grande valley – the beauty, hardship, and resilience, the collective tears of joy and sorrow shed by the area’s peoples, all eventually making their way back to the river that gave birth to the city.

Las lágrimas del pueblo is a map of a portion of Albuquerque’s flood control system and network of arroyos that functions as a musical score for composition or performance. The map presents eight musical sections representing six arroyos that distribute storm water into the North Diversion Channel which, in turn, distributes water into the Rio Grande. The front of the map provides an abstract form of graphic notation that musicians use as a stimulus for composition or improvisation, while the back of the map provides some additional parameters and sonic material for each of the sections. The score can be realized in live performance or fixed media, using any instrumentation, electronics, recorded audio, or other means.

The structure and material for Las lágrimas del pueblo is derived from visual and sonic elements experienced by the artist at locations along each of the arroyos and the Rio Grande as well as from a variety of New Mexican folk songs recorded, transcribed, and catalogued by John Donald Robb and preserved by the Robb Musical trust and UNM’s Center for Southwest Research. It reflects the physical infrastructure and environment of the flood control system as well as local stories and folklore told through song.

The accompanying online material includes videos containing musical realizations of the map and photographs taken at the locations.

-

7 years

by Kel Cruz

Maps typically aid us in navigating where we want to go, but they also can be a tool to show us where we have been. “7 years” is a chronicle of the memorable pathways that I have traveled since moving to Albuquerque in 2014.

While mapping these pathways I only illuminated places that I could distinctly remember and mentally picture in my mind. During my process, I used Google Maps as a reference for street names (but refrained from using the street view) and also wrote reflections in a journal that were categorized by seasons to jog my memory. The final work is an exercise in memory but also a visible reminder that no matter how well we believe that we know a place there are always parts left undiscovered and unnoticed and there is a kind of wonder in that.

The detailed vector map used for the baseline of this map was created using OpenStreetMap, overpass turbo, and mapshaper. Documentation to get anyone started in making their own detailed vector maps of any city can be found here.

-

Murals by Dimitri Kadiev

by Daniel Paul Davis

On the digital map list, I have included eight YouTube video thumbnails embedded with links. The videos feature each individual mural accompanied by a brief musical impression. There is also a brief bio of Dimitri Kadiev at the bottom of page one along with other Dimitri links that I did not create.

Page two features three “traditional” map sections with lines drawn between a photo thumbnail of each mural pointing to their general location on a street map. Page two is more typical of a map, but the actual addresses are only listed on page one.

-

The NDN in the Crossroads

by Miriam Diddy

Interactive components:

Access a Google Earth Voyager Tour of the places influencing this indigenous map making.

I along with many other people continue to live on the traditional Tiwa homelands of the Pueblos of Sandia and Isleta – also known as “Albuquerque.” As a Diné and Hopi woman, I often wonder how my ancestors traversed through this place? What concepts of navigation did they follow? How did they see, cognitively map and imagine in their mind? What marks did they leave on the landscape? Counter to Western methods of mapping, this map explores indigenous concepts of navigation and place. The circular map is a schematic representation of geographic landmarks and features iconic to the region. It is oriented with east at the top. The background is washed with colors of the Albuquerque sunsets and night skies with glimpses of constellations. At the center are natural landmarks: the Sandia mountains to the northeast, the Foothills to the southeast, Nine Mile Hill to the southwest, and the Petroglyphs to the northwest. These four landmarks are divided by the Rio Grande River. I imagine my ancestors and generations past may have crossed these local landscapes, stood where I stand, and gazed up at the very same skies.

Fast forward to present day Albuquerque, this land has been settled and shaped by a diverse range of communities, both past and present, each bringing their cultural, social, environmental, and physical influences to the land. The landscape is now characterized with a gridded network of roads and urban streets. As shown on the map background, major street names are now written and tagged over the canvas of the sky. The land has been cut by two major highways, I-40 and I-25, which has created a crossroads for navigation in the City. This intersection becomes a center and turning point for travelers. It has divided the City into four quadrants as depicted by the four white crosses near the borders. This urban pattern of settlement is juxtaposed against the beauty of the landscape that has existed since time immemorial and connected to the original people of this place – Pueblo, Diné, and Apache. At the crossroads, Albuquerque is now a hub of directions, a hub of culture, a hub of daily activities, a hub of City life and a hub of diverse people. We each have a path to cross this hub. As we create our own path, we can honor and respect the Indigenous people – our ancestors, present relatives, and future generations that will continue to inhabit and steward the land of Albuquerque.

Ahéhee’ / Askwali (Thank you)

-

Trinity of Hybrids Map

by Sean Paul Gallegos

This map is a hybrid of culture, iconography and techniques. The inspiration came from European tapestry woven maps and the traditional weaving of the Southwest. Reflecting the cultural mix of its creator. The icons chosen for the map are unique to Albuquerque. From the remembrance mural of Vela Art featuring New Mexico’s own hip-hop legend Wake Self who tragically passed away in 2020 to the giant arrow on Carlisle to the Paul Bunyan that graced route 66 for decades. These icons resonate culturally as well as creative markers of the city. The mixture of techniques used to create this map are a hybrid of traditional tapestry weaving and hand embroidery. Once again reinforcing the hybrid nature that represents Albuquerque.

-

Slow U Ass Down, A Map of Dr3Amz

by Haley Greenfeather English

For a few years, I have been recording my dreams. Mostly, pieces of fragments of moments I could remember before my morning coffee. “Slow U Ass Down, A Map of Dr3Amz”, is a visual mapping of my dreams from August 2020-March 2021.

-

Rio Grande Ephemeral Sandbar at the San Antonio Oxbow

by Lenore Goodell

Digital file created with CorelDraw using Google Earth imagery as base map and track data collected with a Garmin device.

This map refers to a photographic essay at lenoregoodell.com.

-

Garage of Mysteries

by Marya Errin Jones

The Tannex is a live music venue, videodrome, zine library, lecture garage, divining rod, and tuning fork near the crossroads in Barelas, the oldest village in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

This map represents every public performance produced at the Tannex since its founding in 2013. The dates and titles of shows and names of performers blend and blur, like electric tributaries emanating from the photo. Touring acts and local acts share the stage with women and/or BIPOC on every bill. Over the years, until 2020, thousands of people gathered at the Tannex. Hundreds have performed on stage, in a safer space originally intended to be only a garage, nothing more. The Tannex is living its best life!

By day, the Tannex doesn’t look like much, just another dusty room, caught in the inevitable and indifferent floodplain of gentrification. At night, the Tannex glows like a lighthouse, near the Rio Grande river. This garage is a place where are all welcome, a refuge for artists creating and living in the margins.

The back of the map represents visitors to the Tannex who took selfies in the bathroom, a permanent art installation created by ¡brapola!

To fold this map into a mini zine, follow these video instructions by the San Mateo Public Library.

-

Disrupt Displacement

by Tina Kachele

This map highlights six of the many locations around Albuquerque where unsheltered community members make their home, and where the City of Albuquerque continues to enact sweeps, displacing people and often confiscating or throwing away their homes and belongings. Despite CDC guidance against disrupting encampments in this way (due especially to the pandemic), our city continues this practice. With many barriers to permanent, affordable housing, evictions and income disparities on the rise, and a shortage of accessible, trauma-informed, and compassionate services for people living outside, this map is a call to action for the City to #StopTheSweeps. Instead, our city must create and/or expand programs that support people where they are and allocate resources for a range of housing options–including various ways of living without traditional shelter, among them community-driven tent communities.

We also recognize that this practice of displacement (or forced relocation) has deep roots in the settler colonial violence that continually displaces Indigenous people(s) from their ancestral lands, and similarly marginalizes/displaces BIPOC/low-income/LGBTQIA+ people, and people with disabilities. Along with the contemporary, daily violence of these practices, the brutality of displacement is connected to and triggers historical trauma(s) for those directly experiencing the impact of white supremacist policies.

Create Communities of Care

We are committed to Creating Communities of Care built on a model of solidarity not charity. At each location on the map, we have placed painted rocks,* bringing joy, and the presence of community members, back to the places where sweeps continue to happen. #WeBelong and #WeCannotBeErased are calls to action asserting the vitality and beauty of our friends and neighbors who live outside. Since March 16, 2020, ABQ Mutual Aid has served over 60,000 community members in all 17 zip codes in the Albuquerque Metro Area and beyond. These care packages are prepared and delivered with love (to both housed and unhoused community members), with no criteria to meet and nothing asked in return. Our work is done and sustained by the generous donation of time, energy, and resources from community members in Albuquerque and beyond.

We know that when we listen to community, we find the best solutions. We are building the world we want to see and we have seen that it can work.

*This project of placing painted rocks at each location will be ongoing.

We invite you to paint a rock and place it at one of the locations on the map.

We hope you will then share a photo of your rock on our Facebook page.

Call to Action

Contact the Mayor’s Office at 505.768.3000 and demand that they #StopTheSweeps.

Our city must build programs that support people where they are and recognize the need for a range of housing options—including various ways of living outside, among them community-driven tent communities.

-

The Taylor Ranch Library Project

by Sarah Kennedy

There’s a website associated with the map that can be explored here.

Part personal narrative, part deep-fried meme, The Taylor Ranch Library map is a big dose of 90s/00s nostalgia on a printed page.

Drawing from her experience living near a landmark in her neighborhood, Sarah Kennedy has adapted a vintage video game console ad to playfully takes you on a tour around all of the most radical and tubular sites of a library on Albuquerque’s westside.

After visiting Sarah’s version of the Taylor Ranch Library, you too will know all the killer spots to go sledding and dare friends to spelunk in a tunnel.

-

The Corrosive Elements of Teenage Experiences or: The Satisfaction of Not Needing Revenge

by Alec Loeser

Personal places of power; an area that is inherently or imbued with the magic and terror of youth. I wanted to give visual representation to these small portions of the city and how each agitated my heart. Every location I photographed was a boon to me in some way or other throughout my time growing up. My friends and I have always wandered, sometimes as far as we could go in any direction (generally without a specific destination). This is how I learned Albuquerque, through a series of fortuitous missteps, parachuting into different lives. This city was built on the genocidal actions of colonizers. The animals in the painting represent the parts of the city that stay entrenched despite this. They are the art and life that still grow from the spaces in between. The land and people whose unfettering refusal to change or hide keep it ours. This is a good place. A good place to hate, a good place to love, my tender indifferent home.

-

South Valley Acequia

by Lorenzo Lopez

Water is sacred here in New Mexico. We live in a semi-arid desert area of our country. Droughts have come and gone throughout time. Indigenous communities already had a system of irrigation when the Spaniards arrived. Our ancestors always worked with the land and rivers to sustain the agriculture, pueblos, villages and style of life.

The acequias that are found in the South Valley of Albuquerque bring life to our small farms who grow crops to provide fresh vegetables and fruits to be eaten and sold locally. The water that flows through the acequia veins is celebrated. It is a way of life in our community.

The map I have drawn shows the water flow and emphasizes the green life that sustains not just the valley floor, but the wildlife, cottonwood bosque and the city of Albuquerque. Sin agua no hay vida.

-

Holy Places

by Sonia Luévano

The title of my map is “Holy Places”. The points on my map, being few and far between, have been places where I have found peace, joy, and inspiration during my time of quarantine, and as the mother to a newborn during Covid. To coincide with the title and theme, I did this map in the style of medieval maps done during the gothic era taking symbolism from iconography of the time to describe the points of interest.

-

Books and Reading in the Albuquerque Area

by Pam MacKellar

Books and Reading in the Albuquerque Area is a map that guides visitors and residents alike around the Albuquerque area using books, reading and learning as a focus. When traveling in a new area I usually look for some of my favorite places—bookstores, libraries, art galleries and museums—as a way to learn about an area and how to get around. Book lovers and readers are encouraged to use this map in the same way. The recognizable landmarks, the Rio Grande, I-25 and I-40 will orient you as you travel. The places identified on the map include:

quiet spaces to read

unique public libraries

independent and used bookstores

historical buildings housing books

southwest collections, local cultural and historical information

The artist book, Books and Reading in the Albuquerque Area was inspired by maps of the greater Albuquerque area and my imagination. The center spread correlates to the main map created for this project, while the other pages are my interpretations of maps using the recognizable landmarks in imaginary ways.

The 2-sided downloadable map is designed to spark your personalized exploration and discovery of the Albuquerque area with books and reading as the main focus. One side of the map is the center spread from the book, showing the numbered book icons. The reverse side has descriptions of the places on the map including addresses, and instructions on how to fold the map into a book.

-

I Wrote You a Poem

by Zahra Marwan

Marwan’s work is a delicate mix of nostalgia and reminisces along with details from day-to-day life. She is so proud to call both Kuwait and New Mexico home.

-

Albuquerque: Experience the World

by Karen Jones Meadows

I didn’t know what a compass rose was, and neither did anyone else I asked. I’ve learned they’ve been around at least since the 1300s, and that sailors tattooed themselves with them hoping for luck on treacherous seas. They are also called wind roses. Makes perfect sense since these instruments measure the speed and direction of the wind. Wind, air, breath—seen as one—is understood as the element of communication in most spiritual belief systems. Communication in all of its forms is the key, the necessity, and eventual reality of all harmonious living. My compass rose map is a reflection of people’s desire to share on multiple levels their cultural uniqueness and to learn about others with an appreciation that we are inextricably connected. We are a mosaic of different patterns that fit together as one global family anchored—at least for a while—on the common denominator, earth. Willingness, communication, and love in action = Harmony.

Participate in events presented by the various communities on this map. Copy the labels and compass roses and add additional events to your take-away map or design your own map highlighting your favorite organizations and experiences. You can also create an event. Express your dynamism as a part of the world mosaic.

-

Cartography of the Heart: Reclaiming Our Sacred Interconnection

by Bobbye Middendorf

Map Meditations and Poetry (links to audio and text) at the following: Spoken Word Alchemy, poetry and centering/grounding meditations for sacred re- & interconnections

What if Mama Gaia herself, the Living Land, pockets of wild or less-tamed nature, can be recognized as the living sacred being with whom we are invited to partner? How might this look? How might it be mapped so as to amplify, magnify, and reclaim this relationship with Mother Earth?

What more is possible when we make the inner space and outer commitment to slow down, commune, listen, imagine, and dream together with the sacred, living land — in a sacred space of reverence and conscious interconnected partnership with Mother Earth? This map invites those willing to slow down to become students of the wisdom of Mother Earth; To hear her whispers broadcast, transmitted outward in every moment. This connection point is within each being, the mysterious inner true listening center.

Disconnected from our depths of inner space, we’ve cut ourselves off from the deep Earth magic that can heal unspoken yearnings, disconnection, and grief. The Living Land and sacred ground of Mother Earth offer solace and healing when we can consciously connect to the wholeness available through interconnection with the Land. The notion of Living Land appears to be a magical conception — except for those for whom it is deep truth embodied. This is one of the living legacies of the indigenous peoples on whose land we now are guests. How can we begin to encompass such embodied magic? How might the Living Land guide us, simultaneously, to heal in partnership with her and with the peoples who took care of the land for eons?

The Living Sacred, as mapped in Cartography of the Heart, begins by reclaiming the sacred and magical. It’s a weaving of healing-into-greater-wholeness to amplify this sacred partnership. Through messages, meditative practices, poetry, mixed media collage, invisible alchemy, and grounding experiences, all are invited into aligned harmony with the Earth as living sacred Being. We are co-creators of this sacred partnership, for birthing a new reality where all life forms, all beings, FLOURISH.

This map includes 7 elemental nature spots around Albuquerque to engage with the living land. Cartography of the Heart: Reclaiming Our Sacred Interconnection is a map encompassing multiple fractal facets — a visual collage marked with 7 sites and 3 levels of varied depth-interaction possibilities. Beyond the “official” messages from the institutions responsible for each site, (in the links on side 2 of map printout), the artist has created poems and grounding meditations to deepen the experience, inspired by the sites, Mother Earth, and the Elements.

This second layer of mystic connection opens an invitation for humans to engage, slow down, listen from a grounded center point of inner stillness. Such messages emerge in deep listening and communion with the Living Land herself. Both official and mystic messages are part of this project, all inextricably intertwined. Each person is invited to discern the mix of outer and inner that will be of greatest service. All are encouraged to cultivate a deeper and nuanced interconnection with the Earth and the indigenous peoples who took care of the living Earth, our Beloved Mama Gaia, for so long.

Key for locations in Cartography of the Heart: Reclaiming Our Sacred Interconnection (Map)

Light Green Circle: 1, 4, 7 — Mid-level interaction with nature, with some curation

Dark blue Circle: 2, 3 — Greatest wild nature connection & least human intervention

Lavender Circle: 5, 6 A-B — Highly curated cultural institutions, least nature interaction

-

Albuquerque City Limits

by Arthur O’Donnell

Albuquerque’s municipal footprint has been compiled like a jigsaw puzzle with 842 pieces of irregularly shaped parcels of land added from 1882 to the present day. This map and photo project documents the city’s current outer boundaries to frame the history, character and urban/rural interface of New Mexico’s largest and most diverse city. Along the periphery are ancient petroglyphs and volcanic fields, modern military/industrial complexes, farms and precious open space areas that contrast with the urban auto-centered urban culture within the city limits.

Albuquerque’s profile is made up of at least two hundred inflection points, few of which are 90-degree corners. There are ragged edges and sharp points, curves and lines that follow river banks, arroyos and irrigation ditches, large building blocks of mostly-undeveloped land, and what appear to be multiple islands off the coast but are parcels tethered by “shoestring” annexation politics. These latter properties proved to be among the most contentious additions to the city, when annexation battles raged for decades in both north and south valleys.

Annexations were also limited by natural and geo-political boundaries: Native American pueblos to the south, west and north; inviolate military lands to the southeast, and of course, the Sandia Mountains and Cibola National Forest that define the eastern boundary line.

Even life-long residents have never visited some of the areas along the border of what has been described by urban chronicler V.B. Price as: “A city at the end of the world…with a distinguishable edge.”

The backside of the give-away map includes geospatial information about 40 stops around the city periphery with those on the map highlighted and color coded: landmarks, street addresses, elevation, latitude/longitude, date of annexation into the city (if applicable) and city ordinance date and reference number.

-

Albuquerque Remote Viewing

by Adrian Pijoan

I like to explore cities I’ve never been to virtually. I go to Google Street View and walk the streets of places on the other side of the globe. I fly through the 3D projections of cities on Google Earth. I visit Yelp and look at the menus of faraway restaurants and imagine what I’d order if I could ever visit. I love doing this, but I also realize that when I visit cities virtually my vision of them is mediated by the gaze of Big Tech companies with their own agendas, ideas, and limitations. The city is only rendered as accurately as their satellites can see.

For this project I began exploring the Google Maps 3D projection of Albuquerque, New Mexico — the city I call home. The 3D geometry of downtown Albuquerque produced from these satellite images is bizarre and distorted. Buildings bend and collapse at strange angles. Notable landmarks become tangled masses of overlapping triangles. These bizarre 3D models got me thinking about remote viewing, the practice of psychically seeing or sensing a distant place or person. During a remote viewing session images and perceptions frequently come through in distorted fragments.

Thinking about remote viewing, I took these strange, broken geometries of Albuquerque and transformed them into dreamlike structures — a vision of downtown remotely viewed from my computer. Through this exercise Albuquerque Remote Viewing became a reflection on how the ever watching eyes of big tech companies view us and how their gaze can distort our reality. My hope with this map is to inspire others to transform this gaze into new constructions that we feel ownership over.

-

Reeds in Mud

by Jonathan Reeve Price

This map explores the San Antonio Oxbow, a bend in the Rio Grande as it flows through Albuquerque. The river used to curve into the bluff on the West side, south of Montaño, east of Coors. But the current was eating away that giant sand dune, threatening the streets and houses above. So the Army Corps of Engineers dug a new channel, leading the main flow of the river away, leaving a backwater behind.

This wetland offers a lush habitat for birds, animals, and plants. We can see the arc of this marsh from satellite images and topographical maps. But to appreciate the beauty of this open space, we need to go down to the edge, and look at the reeds, the willows, the tangle of trees. The Oxbow is not just a shaded line on a map; it is a living world.

This hi-res image combines a map with a photograph and a digitally manipulated remix of those materials, plus a text label identifying the location.

On the back of the map, there is a poem speaking up for the birds, animals, and plants that give this land life.

Explore the whole series:

Rio Grande Wetlands: Trees at Dawn

Rio Grande Wetlands: Entangled in the Oxbow

Rio Grande Wetlands: Bluff Through Willows

Rio Grande Wetlands: Through the Fence

-

Esta es Nuestra Calle

by Eric Romero

My submission is the visual interpretation of our distinctly New Mexican cruising culture. Washing and waxing on Saturday afternoon, Mass on Sunday morning then down central for a cruise. Windows down, one hand on the steering wheel and two fingers in the air. The only constant is the rosary hanging from the rear view mirror. The year is 1949 or 2021, the only rules are give respect and keep your ride clean. A weekly pilgrimage of chrome and rubber, a procession of the present that honors the past and the future. Burn em, drop it, turn it up. I see you.

-

Merpeople of the Rio Grande

By Endion Schichtel

This map was made by the Merpeople of the Rio Grande to invite all humans to love our water sources and explore the Bosque, the forest surrounding the river. Water is precious in our dry desert home. The water humans use in Albuquerque comes from an aquifer underground and the Rio Grande river, both of which are being used to their limits.

I work in Albuquerque as a local biologist and water resource specialist, using art and circus to communicate science. I left New Mexico for several years to travel and work and did not intend to come back…but inevitably did, as we Burqueñxs so stereotypically do. Shortly after returning, my father died suddenly. The mermaid photograph bubbles on the map are where I found shelter and healing afterwards. I will forever be grateful for my friends, the forest and the river for holding space for my grief and helping me become again.

Everyone can act like Water Warriors and use less water each day at home, and leave enough for the merfolk. Come look for us and the other magical creatures of the Bosque!

-

A Sandhill Crane’s Guide to Albuquerque

By Marianne Shifrin

The Rio Grande River, which passes through Albuquerque, is central to Sandhill Cranes’ migratory journey every fall and late winter. The birds travel from their breeding grounds in Alaska, Canada, and Siberia to their winter home in New Mexico, Southeastern Arizona, and northern Mexico. Albuquerque serves as the northernmost border of their winter habitat along the Middle Rio Grande Valley, and so Albuquerque residents are privileged to share their city with the Sandhills from October through February each year. I have created this map from the perspective of the cranes as they fly into Albuquerque. Some simply pass through, but others settle down here in town as “snowbirds.” I colored in the crane migration patterns on a North American map, and overlaid it with a map of Albuquerque to demonstrate how interconnected their migration is with the city. The images on the map are photographs that I took of the cranes enjoying their winter stay. Click on each image for an illustrated audio representation. I recorded the audio clips on clarinet, pandemic style – alone and in my apartment – to portray the beauty, humor, and fascinating behavior of these birds.

The links below accompany the various stops on the map, with pictures and music performed by the artist.

Cranes roosting on the Rio Grande

Cranes arrival at Bosque del Apache

These websites are great places to start for learning more about cranes:

-

Skateboard Ditches of Northeast Albuquerque

By Samuel Swift

On my map you will find the following things: skateboarding snakes, ditches (arroyos) that are well suited (and world renowned) for skateboarding, Orbit the Isotope riding a nuke (after Kubrick), several police cars, cacti, La Llorona (specifically a rendition of her designed by the city of Albuquerque in the 1990s to keep people from skateboarding in the ditches), the place where police shot James Boyd in 2014, and finally a snake eating a brand of cereal that is endorsed by a skateboarding snake. The places named on this map are “Concussion,” “Montgomery,” “Indian School Ditch,” two ditches I do not have names for, and “4 Hills”. Also, there is Tramway Blvd., Juan Tabo Blvd., I-40 and Route 66 (Central Ave). I am told “Concussion” ditch was so named in the 1980s by skateboarders. “Montgomery” is my name for the short fast ditch that runs near the street bearing the same name, which was named for Eugene Montgomery, a homesteader from the early 1900s according to the Albuquerque historical society. “Indian School Ditch” takes its name from the street of the same name, which is a remnant of the harmful and unjust colonial boarding school system of re-education and assimilation of indigenous children. The “4 Hills” ditch takes its name from the Four Hills neighborhood, which backs up to Kirtland Air force base and what may be 2500 nuclear warheads. “Tramway” takes its name from our tram up the Sandia mountain. According to the Albuquerque historical society, no one really knows who “Juan Tabo” was. I-40 and Route 66 (now Central Ave) are both now what was America’s famed Route 66. I am not from this part of town so there may be many landmarks I missed. Finally, if you are a (pedantic) skateboarder and you noted a ditch I missed, I apologize!

Links

Some ditch skating footage I filmed specifically for this project

-

Albuquerque Lockpicking Map

By Hannah Reiter and Kelli Trapnell

Albuquerque Lockpicking Map website.

To use the map, you’ll start at the entrance to the Bosque near the Rio Grande Nature Center. The combination to the first lock is 7572. Read the pieces of the story inside each lock (or on this website, if your lock is missing a story piece for some reason*), and follow the instructions to choose your next destination. The path you choose might lead you to another lock (for which you’ll be provided the combination) or to a QR sticker, which will have the password for the post on this website written on the sticker.

Follow the story through each of the locks and stickers to discover all of the possible endings and all of the possible narrative paths your journey might take. The photos above are of each of the actual locks and stickers—if you can’t find the lock or sticker you’re looking for right away, use the photos for reference. Sometimes the sticker might be located near your destination, but not inside of it—try searching the street signs on the nearest intersection.

This story map is meant to be a game, a process of discovery, and a puzzle to solve. Its contents are rated PG and are appropriate for kids and adults alike. Have fun!

-

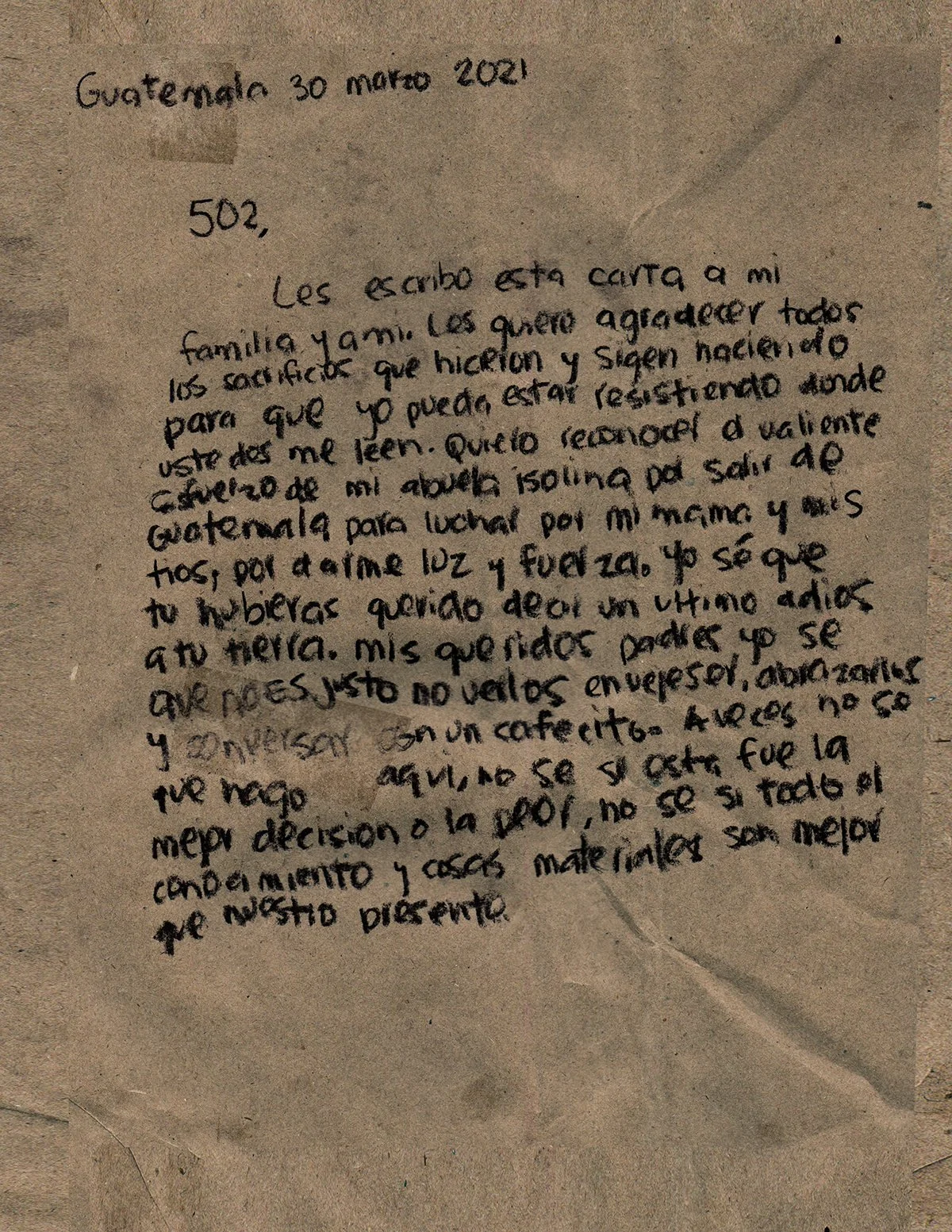

502 Immigration

By Martín Wannam

My map addresses my immigration, specifically addressing my feelings toward my displacement, from Guatemala to Albuquerque. I look at the gesture of writing as a way of mapping my experiences toward the feeling of missing my parents and acknowledging my grandma’s migration and death; juxtaposing the feeling of my family to the ones related to my country.

-

Lungers’ Row

By Emmaly Wiederholt

“Lungers’ Row” explores the row of sanatoriums around Central Avenue that treated tuberculosis patients 100 years ago. In the early 1920s, my great grandfather Francis J. Lingo was one of thousands who moved to New Mexico to “chase the cure.” Tuberculosis was one of the deadliest diseases in the early 20th century, and many physicians advised patients to seek relief in high dry altitudes. Albuquerque was transformed in a few short decades into a thriving health economy based on treating the influx of lungers.

This map shows the five main sanatoriums where my great grandfather might have sought treatment in 1921: St. Joseph Sanatorium, Southwestern Presbyterian Sanatorium, Murphey Sanatorium, Albuquerque Sanatorium, and Methodist Deaconess Sanatorium. The miniature maps showing the grounds of each sanatorium are taken from 1919 Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of Albuquerque. As you can see, they were positioned on and near Central in such a way that the area became known as “Lungers’ Row.” I revisited those sites to find what is there today: parking lots, office complexes, even major hospitals.

I was photographed at each site by Pat Berrett in 1920s pajamas and loungewear sewn by Cathy Intemann with the intention of depicting a lunger out of the past. As Erna Fergusson is quoted in Nancy Owen Lewis’ book Chasing the Cure in New Mexico, “People stroll along the streets in bath-robes and slippers.”

Lungers and their families significantly altered the culture and demographics of New Mexico; according to Lewis, tuberculosis patients made up an estimated 10 percent of New Mexico’s population in 1920. But now the fashionable lungers are gone; little evidence or awareness remains of this health industry that dominated Albuquerque a century ago.

I wanted to draw the parallel between 100 years ago and the present because with 2020 came the experience of living through another health crisis – COVID-19. As I researched how tuberculosis had impacted New Mexico, I was struck by the similarities of the diseases: COVID-19 and tuberculosis both impact the lungs, in both eras there was an emphasis on spending time outdoors in order to achieve maximum health, and loungewear became vogue during both eras. These are a few of the similarities my map touches on among many more similarities between the diseases. Through “Lungers’ Row,” I want to create awareness that the past is never as distant as we think.

Photos by Pat Berrett, costumes and calligraphy by Cathy Intemann, 1919 Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of Albuquerque courtesy the Library of Congress, other materials used include automotive paint chips and crushed eggshells.

-

A Map of Insects in Our Yard

by Emma Eckert

Richard Louv, in Last Child in the Woods, writes of an old native saying: “It’s better to know one mountain than to climb many.” In this case, my well-known mountain is my home and surrounding land, a city plot less than two-tenths of an acre, yet full of mystery and tiny, unexplored worlds. When I moved in to this place with my husband ten years ago, we were greeted with a handwritten card from the children of the previous owners – the only others to live in this house. Juan and Juanita bought the house when it was built in 1954. They raised their three children there, and all but one of the family members was deaf. Contrary to the inspector’s decree that our doorbell did not work, instead it was hooked up to a set of lights that would flash when the doorbell was pressed. We kept the lights, and to this day, my keen eyesight (I thought, anyway) still very rarely picks up on the flashing of the lights. My hearing mutes my other senses.

We moved in during the month of March, when the dormant yard was just beginning to reawaken. For the first few years, we watered and tended the grounds, just seeing what was already there and identifying the new plants that would spring up, and finding some surprises in the animal kingdom, as well. A few box turtles crept up from their winter slumber to stroll around the back yard, and we named the two large goldfish in the pond Juan and Juanita. Sometime around the third or fourth spring, we decided we’d like to plant an edible landscape so any new plant additions would need to serve that purpose (though upon one spontaneous plant buying spree I was lamenting the restrictions as I eyed some showy bulbs, and a kind woman approached me and said something about loving her garden because it feeds her soul, and from then on it was fully acceptable to plant something of which the ‘only’ sustenance it provides is food for the soul). Over the years we became quite proficient at identifying all of the ‘weeds’ that would also come up in the yard, and I was surprised at first to learn that many of the volunteers that readily sprouted up in the yard were either edible or useful medicinal plants, and so they, too, became part of the seasonal march of growth. Along with the growing jungle in our yard, our family grew, too, and two sweet boys arrived earthside on summer days, five years apart. As they’ve grown, so has their knowledge of the plants and other inhabitants of our yard. We frequent the outside in just about any weather, almost every day of the year, building small creations and tending to the plants.

Most years we would purchase new plants to add to our collection, however one year we didn’t buy any new plants. Twenty-nineteen was a year where we made do with what we had at home. In lieu of new, we re-homed several volunteer trees, either to new locations within our yard, or as gifts to our family and neighbors. We dug up dozens of mulberries, a few pink silk saplings, and a couple desert bird of paradise bushes and rearranged or gifted them all to new homes. Making do with what we had was good practice for the year to come.

In spring of twenty-twenty, just as my older son was going on spring break, we prepared ourselves for a two-week stay at home. I usually would shop for a month’s worth of food, and we had plenty of dried foods to last even longer, so two weeks of supplies was not an unusual shopping trip for me. I remember the novelty, or embarrassment, of wearing my mask to the grocery store for the first time. Those two weeks stretched into months and months, and not wearing a mask became more of a discomfort. In the past year, we have, primarily, stayed home. There have been a few trips out in the car, which the boys now view as a wonderful adventure. We’ve gone hiking, or more recently, we went to some outdoor nurseries to search for some additions to our grounds. We planted some token memorials, for those we lost this past year. Over the years, so many memories have been buried in the ground along with new plants. Our yard is full of ghosts, living amongst the roots, intertwined with so many others who have gone before us. And though I cannot see them, I know they are there, hidden away in the folds of the earth.

I know this is a map about insects… so why am I talking so much about plants? The more time I spend here – in the yard, on this Earth – the more the interconnections of nature become apparent, as well as bring out more questions and mystery. The first thing I had to decide upon when creating my map (well, the second thing, after what I wanted my map to feature) was the scale. Because of the fractal nature of cartography, the scale can be immense or minute, and, in theory, you can always move infinitely farther in either direction. With a scale large enough, my map could encompass all of the other maps made in Albuquerque – indeed, all of the other maps of the world, and even out into the farthest reaches of space. Likewise, within any given space, there are tiny worlds to be explored, further and further. There are eddies and surprising twists and turns that are taken when exploring the beautiful complexities when one grows smaller and smaller (or larger and larger), and yet there is even more detail to behold. It is simultaneously mind-boggling and enlightening. The details that emerge along the perceived boundaries can be the most interesting and intricate. If you look closely enough at a tree, all the way out to the tips of its branches or roots, the boundaries between the tree and the surroundings become ever more blurred and complex. The surface of the leaves are exchanging gasses; the roots are taking in moisture and nutrients. The air, water, nutrients – they enter the tree. They become part of the tree, so where do you say the tree ends and the ‘not-tree’ begins?

The insects visiting or living in our yard are there primarily because of the plants, and the plants are there because of the insects, in most cases. The vast majority of our contemporary plant species are pollinated by insects or other animals. For this reason, it felt strange to have an empty space for my map, a rectangle populated by little blips showing where the insects were relative to… well, relative to what, exactly? I looked back over the insect images taken over the summer documenting all the bugs we could locate while tending to the garden. In looking at the hundreds of photos I realized that I relied on the background for the location of the insect. The stationary plant or wall or pathway – those were the guiding features for locating a mobile target at that point in time. Of course, because the location points were taken at a very specific point in time, it is unlikely, should I go back to look at that same spot this next summer, that the same insect will be there in that same spot… However, in many instances, the offspring of the same insects will be there. For example, a flame skimmer dragonfly has visited our pond for the last half-decade or so, and considering the lifespan of an adult, it is reasonable to assume that the visitors each year are different individuals, but perhaps are offspring that have hatched from our pond (we routinely find nymphs in the pond, and shed exoskeletons hanging onto the cattails left by the young as they transition to their adult form). The insects form a particular relationship with, sometimes, very specific plants. In creating the data points for my map, it was interesting to see upon which plants certain types of insects were found, or which plants drew the greatest variety of visitors (hollyhock). Two years ago, when my older son was in kindergarten, he made a project exploring what plants in our yard were ‘bee’s favorites’ – most visited by honey bees. (He concluded that the budding apple tree, the creeping myrtle spurge, and dandelions were the bee’s favorites, and the reason for the project was to help people know what types of plants they could grow to help bees.) This project also involved hiding under blankets with a camera and blacklight flashlight to take photos of flowers like bees might see them with their UV light sense. It was fascinating and fun, and I highly encourage any involvement kids want to have playing outside and exploring the natural world. Currently, our classroom is our home, and we quite often have several different outdoor projects running at once.

As our stay-at-home ‘two weeks’ stretched and grew into something much longer, we experienced the ‘smallening’ of our world. Our entire existence, save the strolls in the neighborhood to visit the dogs we’d come to know on our walk to school – when we went to school – or the hikes into the foothills or extinct volcanoes around our fair city, or my solo trips to the grocery store, our entire existence was in and around our home and yard. We began to use what we had rather than unnecessarily venturing out or further taxing the overloaded postal service. Halfway through the summer, I wrote the following words regarding this subject:

“Using what we have has become a motto, or sort of mantra, around our house. In the ‘before time’, it was easy for me to start on a random project and realize I didn’t have that something, that one thing that I just can’t make the project work without, and so would have to run out and purchase (or order) said thing. There are still projects like that. For example, we were going to repaint the trim on the house, but don’t have paint for it, so that is a project that we can’t do right now. I can think of silly substitutes for house paint, like, say, we could use some muck from the pond to stain the trim a new color… but realistically, that is a project for another day, when restrictions on staying home have been lifted, or loosened, or… reimagined. I know that the home improvement stores are still open right now, but I can’t say that paint is a necessary purchase. If our plumbing goes out and I need to go get replacement pipes, or whatever, sure, but some things can wait. So now, if I’m working on something and run into a block and immediately start thinking, ‘What do I need to get to finish this?’ I try to reframe my question into, ‘What do I already have that would work for this?’ or, ‘Do I need to have this done right now?’”

The vast lengths of time spent at home were a blessing in many ways. Life slowed down. I no longer worried about plans outside the home, but rather in planning (finishing!) projects and activities for us to do throughout the day. I realize that our situation was one of the best-case scenarios and acknowledge that the struggle of many others was far greater than our dilemma of ‘what to do while we stay home’. In saying that, I feel that the past year has provide me with an opportunity to push myself to new heights in understanding myself and my family, to creating new bonds, and to pushing myself to a level of learning and patience that I quite possibly would never have had to do otherwise. Not every day was magical and fulfilling, but even the hard days are good to learn from.

My kids, like most other children growing up in this digital age, are fascinated by screens. They have shows they like to watch and games they like to play. The draw of the electric lights dancing on the screen is great. I’m not opposed to technology. I rely on my computer for a great deal of my work, and I enjoy relaxing movie nights, too. Growing up in this world, it would be a disservice to my children to prevent them from learning how to comfortably navigate, and possibly, at a later date, help improve this digital, mechanical world they have come into. They know no other world, and yet, the electronic aspect of this world is not the only realm that they will explore.

The importance of building a respect for our natural environment and recognizing the relationships between plants and animals I cannot stress enough. I was fortunate to grow up in wild, rural environments, and knew the joys of exploring the high desert woods, hillsides and meadows. This experience was formative in my development and has defined my path both as an educator and scientist, but also as an artist, and maybe most importantly, in my role as a mother. I want my children to wander and explore and ask questions.

This map, I hope, will be a steppingstone, or a starting point, for your own exploration – either alone or with the loved ones in your life. This adventure is multi-faceted, and can lead off down many divergent, yet connected, paths. I hope to spark a new question or plant the seed of an idea for a project of your own.

-Emma

Compass Roses: Maps by Artists - Pittsburgh

Commissioned by the Three Rivers Arts Festival

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

2020